When Amelia first came to me for lessons, she was a fifth grader just starting on flute. She had been playing in the school band for a few months when it was suggested that she enhance her music studies with private lessons. It had been discovered that she was not tonguing any of the notes; that is to say, she was beginning all of her notes with an ‘h’ instead of a ’t’. In flute playing it is necessary to articulate the start of a note or phrase with the tongue. After two or three weeks of trying to coax proper tonguing from Amelia, I wasn’t sure if any progress would ever be made. I felt I had no more tricks up my sleeve. Then it occurred to me that perhaps she didn’t know what it felt like to use her tongue to begin a note. I asked her to pronounce several words that begin with ’t’.

“Say ‘Tuesday,’” I coached.

She rolled her eyes and said, “Duesday.”

To my surprise, Amelia did not use a definitive ’t’ to begin the word.

“Say, ‘talented,’” I asked.

And she answered with something like “Thalenthed,” the ’t’s’ being so soft that they were almost indiscernible.

I pointed out as gently as I could that I couldn’t hear her ’t’s’.

“Really?” she asked, slightly embarrassed.

“Nope. But let’s try a few more ’t’ words.”

We spent the next five minutes saying every ’t’ word we could think of.

“Tomorrow I’m taking my tiger to tango.”

“Tomatoes taste tangy today.”

I suggested she try to feel the tip of her tongue hitting the back of her front teeth. As more ’t’ words were spoken, her enunciation improved. Now that Amelia was aware of the issue, she was able to address it.

The next step was to transfer this new tonguing technique to her flute playing. It was not a difficult transition, and I cheered wildly while Amelia blushed.

After this great success, I looked forward to my next lesson with Amelia. I hoped she would retain her newfound ability to tongue properly, and casually wondered if the technique would influence her enunciation.

As she unpacked her flute, I noticed that there were Jolly Rancher candies being stored in the case, alongside the instrument!

My eyes widened at the sight, and I said, “Amelia! You can’t store candy in your flute case! It is so bad for your flute. Imagine if the candy melted. The pads would be ruined!”

Amelia moaned a bit and continued to assemble her flute.

“Amelia, please take the candy out of the case.”

“Okay, but after the lesson.”

“No, I want you to move them now. Put the candy in your coat pocket.”

Amelia would not budge, and neither would I.

“I will not start the lesson until the candy is out of your case and in your coat pocket.”

To my complete and utter surprise, great, big tears splashed from Amelia’s cheeks. I was moved, but perplexed. I didn’t quite know what to say.

“Amelia, you can’t be that upset about moving some candy. Tell me what’s wrong.”

“It’s nothing,” she sobbed. “I’ve just had a hard day.”

“I’m sorry that you’ve had a hard day. What can we do, now, to shift the focus from the candy and the hard day to celebrate your fabulous breakthrough with the tonguing last week and have a really great lesson?”

She was inconsolable. The tears kept coming!

To her credit, Amelia nonetheless forged through and began warm-up exercises, all the while wiping her cheeks.

After a while, her distress seemed to dissipate, and we managed to have productive lesson.

But I was confused.

“What was the problem?” I asked myself. “Was I too harsh in asking her to move the candy?”

As I often do when I am riddling out a situation with a student, I called my mother, a child psychologist. She has all the answers. She guessed that maybe Amelia’s diet was being monitored at home, and she was not allowed to have treats, so she hid them in her flute case.

“Aha!” I said. “That makes sense.”

Whether or not that was the real reason for the tears and the candy in the case, the insight allowed me to have more compassion for Amelia and the hidden Jolly Ranchers.

Amelia continued to make significant progress in her flute playing over the next three years. She played in two auditioned regional bands in addition to the middle school band.

One day, she came in a bit disheveled, looking very tired.

I asked her what was going on, and she groaned and said, “Eh, too many obligations.”

I usually begin more advanced flute lessons with etudes by Gariboldi or Köhler, which can be challenging to concentration and focus for a young flutist. Amelia’s head was hanging so low that I didn’t see how I could launch into rigorous material.

“Forget the etude,” I said. “Let’s switch things up, lighten the mood, and play duets.”

Amelia smirked at the prospect of not having to slog through the etude, but her posture still belied any feigned enthusiasm.

“Great, we’ll play duets!” I continued. “But first, let’s get in the right mindset. We’ve got to take a stance, assume an energetic posture, and then we’ll be ready.”

“Whah?”

“Let’s go,” I commanded, “Ears over shoulders, shoulders over hips, hips over ankles.”

Amelia did as I asked, and I perceived an immediate shift of mood. She was smiling and standing up straight, ready to play.

“Alright!” I cheered. “Now we’re ready. Let’s make some great music.”

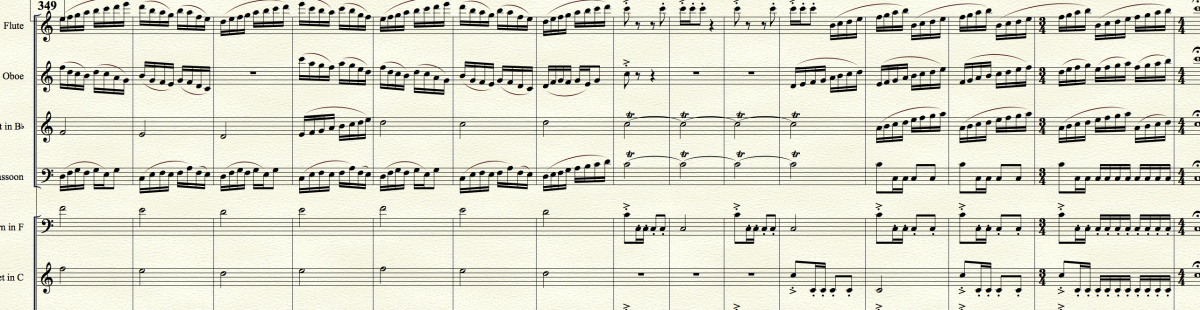

We had a nice time playing duets. I enjoy coaching the students on ensemble playing, practicing playing in tune and keeping an ear out for how the different lines of music interact and weave in and out of each other. At the end of the lesson, I asked Amelia to prepare the tabled etude for next week’s lesson, and she cheerfully agreed.

A week later, Amelia came to the lesson without having prepared the etude. It had been assigned three weeks in a row, and each week she hadn’t prepared it. She complained that it was too long.

“That’s part of the point,” I said. “Etudes demand concentration and stamina to

play well. It’s not enough to play one fast lick. Musicians also have to work on mental focus.”

She promised she’d prepare it for next week, but her demeanor was unconvincing.

“Remember when we first met?” I asked. “You had trouble articulating with your tongue.”

She nodded and looked at the floor.

“You have come a long way from that time, made a lot of progress. You need to respect yourself and your accomplishments by playing that etude!”

The next week she came in and played the etude beautifully. Asking her to honor herself by living up to her own potential is, I believe, a large part of the drive that led her to conquer the exercise.